A driverless Cruise vehicle stalls in the middle of Market Street after getting stuck behind a police car in San Francisco. | Source:Jeremy Chen/The Standard

By Joshua Bote

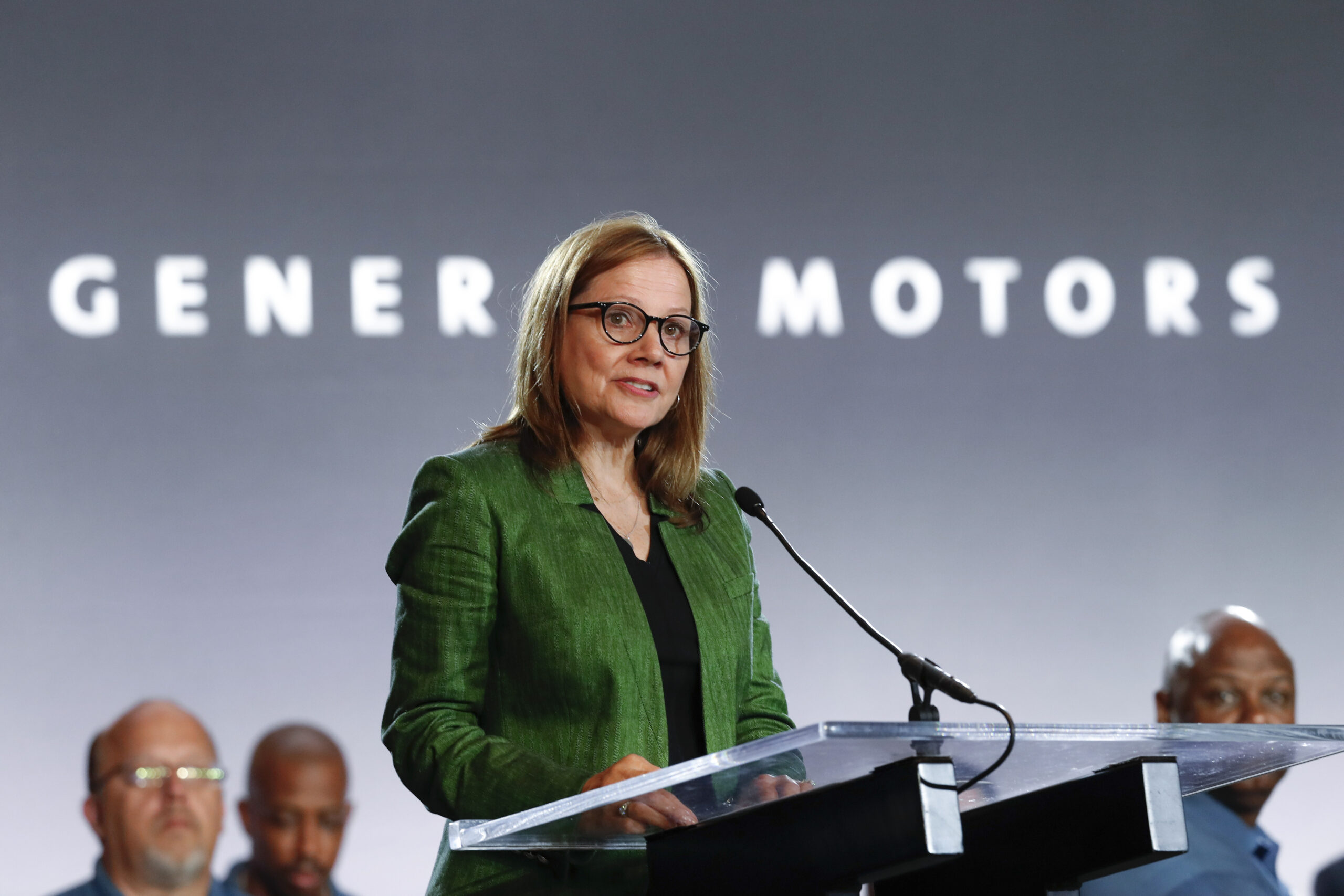

For much of Mary Barra’s term as chief executive officer of General Motors, she’s branded the stalwart automaker—in earnings calls, marketing and public appearances—as a player in the technology space.

Core to GM’s transition was spending a pretty penny to snag Cruise in March 2016, which, at that point, was just a fledgling startup fresh out of the Y Combinator incubator.

Seven years and a few billion dollars later, GM is now making a U-turn away from its large-scale investments in Cruise, begging the question of where exactly the company goes from here.

GM announced it would curtail spending on Cruise in the neighborhood of “hundreds of millions of dollars,” a drop-off that comes as little surprise to observers of the troubled driverless car startup. A string of snafus across San Francisco culminated in a frightening collision that led to a woman being severely injured—she is currently in stable condition—and federal and local probes into Cruise, which pulled its entire fleet from the road.

“When something like this happens, it just kind of puts further doubt in the consumer mind around the longevity, the safety, the adoption,” said Nathan Shipley, an auto industry analyst and executive director at market research firm Circana. “From a business standpoint, you have to pull back and examine things.”

This week’s announcement serves not just as a blow to Cruise’s declining fortunes, but also as a major setback to General Motors, which, until recently, bet big on Cruise as a key part of the company’s future.

“Once we have taken steps to improve our safety culture and rebuild trust, our strategy is to relaunch in one city and prove our performance there before expanding,” a Cruise spokesperson told The Standard.

Auto industry analysts and technology experts who spoke to The Standard say the companies will likely have to go back to basics and rethink previously optimistic projections.

For Cruise, that means a leaner team with a greater focus on sustainable scaling and safety; for GM, that means focusing efforts away from a self-driving, electricity-fueled future to deal with the gas-powered, human-controlled present.

‘They Just Had To Go Full Throttle’

While other carmakers not named Tesla have largely held off on introducing self-driving technology, acknowledging the risks of introducing largely unvetted technology to the masses, Barra and then-Cruise CEO Kyle Vogt made their ambitions clear for Cruise over the past few years.

“For the past five years I’ve covered GM, they’ve always been the technology-forward car maker,” said Gadjo Sevilla, a senior analyst for the connectivity and technology industries at Insider Intelligence. “They would have a bigger presence at a technology show than they would at a car show because that’s really their brand.”

Barra told a South by Southwest crowd last year that she anticipated consumers would be able to purchase their very own autonomous GM-branded vehicle powered by the technology deployed on Cruise vehicles by 2025. Vogt, speaking at TechCrunch Disrupt in September, called the rise of personal self-driving cars “inevitable.”

Earlier this year, Vogt also said Cruise was on track to make $1 billion in revenue by 2025. He stepped down from the company this month.

Meanwhile, Barra said Cruise would be a key money generator for GM, making up to $50 billion in annual revenue by 2030—even though the company was burning through $2 billion a year at the time. (Barra also suggested that GM’s revenue would double to $280 billion in that timeframe.)

Those claims were not entirely unfounded, said Billy Riggs, a University of San Francisco professor and director of the school’s Autonomous Vehicles and the City Initiative.

He explained that the projections likely were based on Cruise moving full-speed ahead on expanding its autonomous vehicle service and rolling out its higher-capacity Cruise Origin driverless van. GM has since paused production on the autonomous van.

“Unlike Waymo,” Riggs said, “they had a really aggressive scaling strategy.”

Integral to Cruise’s rapid growth was spending a ton of cash to expand into new markets and push forward Origin’s development, he added.

“Cruise felt they just had to go full throttle—no pun intended,” said Sevilla, who noted the company has burned through $8.2 billion since 2017. “And with that comes the danger of not really being able to anticipate real-world situations.”

In a stockholder letter released in July, shortly before Cruise secured state regulatory approval to expand in San Francisco, Barra pointed to Cruise as one of its “highest-impact growth initiatives.”

In an apparent effort to maintain its first-mover status, Cruise, according to reports and former employees’ accounts, accelerated too quickly and eschewed safety in the process. Bloomberg reported last week that Vogt allegedly softened safety review metrics in order to expand nationwide more quickly.

Barra said Cruise is undergoing an independent review alongside its plans to relaunch in one unspecified city. That doesn’t answer the question of whether Cruise can regain the public’s trust. Even if California regulators reinstate Cruise’s permit to operate, Sevilla and Shipley say the stain of the past few months will still linger.

“You know, ‘Self-driving car runs over and drags pedestrian’—that’s such a shocking headline,” Shipley said. “That’s all a consumer has to read. It puts doubt in their mind.”

Rebuilding Public Trust

It will be crucial, Shipley said, for Cruise to rebuild public trust and focus on the measures it’s taken to ensure a safe experience for drivers and pedestrians alike. That stands in stark relief to Cruise’s pre-approval strategy, where it publicly condemned human drivers’ recklessness.

Part of Cruise’s future strategy, Riggs says, could include partnering with other companies on operations—letting Cruise focus on developing the hardware and software.

Waymo, for example, recently partnered with Uber to sell its services on the Uber app in Arizona. Waymo is owned by Google’s parent company, Alphabet.

But all of the experts agree that it’s not over for Cruise—or for the self-driving car industry—just yet.

“They’re in a good position,” Riggs said. “They have cash, they have proven technology and they have assets that can be ready to scale.”

For now, General Motors’ approach appears to be pulling away from its tech future. “The profitability and cash generation in its traditional, non-electric, non-self-driving vehicles is still strong,” a letter to GM shareholders on Wednesday stated.

Cruise, as a result, has moved into the background.

“Right now, they’re licking their wounds, which is going to go back to the areas that they know they can control,” Sevilla said.

GM’s self-driving cars are likely going to be put off for a while. Despite Barra’s promises that they would come by 2025, Riggs says it won’t be a “financially prudent nor realistic pathway” for the company’s autonomous vehicle future.

The current reality and Cruise’s future prospects are a far cry from how Barra likely felt as the company was gaining prominence. A promotional video, released in early 2022, featured Barra riding a Cruise car named Tostada in San Francisco with Vogt, who had just been appointed interim CEO.

“I really think that the apprehension that some people think they have is going to dissipate extremely quickly when they get the experience,” she said, later adding, “I feel like we’re making history.”